Without a doubt, our health has been protected and promoted by medical devices, from diagnostic tests that never touch a person to implanted products that stay for a lifetime. However, with increasing value comes increasing risk. For example, if an implanted device is necessary to keep a person’s heart rhythm stable or for a person to walk, the failure of that device could lead to serious problems. Life isn’t perfect, and problems can arise. When problems arise in a medical device, the affected devices can be recalled – this can be an effective step for those devices not yet used but a very difficult situation for devices in use. Furthermore, when a recall is issued, it casts doubt on the device type or brand and questions the research and review that allowed it to come to market. Knowing how to address recalls effectively and learning from past recalls can help researchers and device manufacturers protect and promote health.

Of course, not all recalls are serious. FDA manages medical device recalls and similar information by the following classification scheme:

• Class I recall: a situation in which there is a reasonable probability that the use of or exposure to a violative product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death.

• Class II recall: a situation in which use of or exposure to a violative product may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health consequences or where the probability of serious adverse health consequences is remote.

• Class III recall: a situation in which use of or exposure to a violative product is not likely to cause adverse health consequences.

• Market withdrawal: occurs when a product has a minor violation that would not be subject to FDA legal action. The firm removes the product from the market or corrects the violation. For example, a product removed from the market due to tampering, without evidence of manufacturing or distribution problems, would be a market withdrawal.

• Medical device safety alert: issued in situations where a medical device may present an unreasonable risk of substantial harm. In some cases, these situations also are considered recalls. [i]

Most recalls are done voluntarily by the manufacturer and conducted under a manufacturer’s own initiative. The FDA does, however, expect companies to assume responsibility for voluntary product recalls including follow-up checks to ensure the recall was successful. The FDA’s role is to monitor recalls and assess the adequacy of the firm’s action. [ii] Only in rare cases does FDA need to exercise its authority to issue a recall order.

The FDA maintains a reporting structure for both mandatory reporters such as device manufacturers and importers, as well as health care providers to report medical device problems. In addition to this passive system, FDA also monitors device problems actively.[iii] Most manufacturers do their own monitoring of their products’ safety in some fashion. A more systematized approach of post-market follow-up studies is occasionally required by FDA for serious risk devices that are approved through the formal IDE process.

A short review of past recalls can provide some insight into the safety of medical devices. Between 2018 and 2022, there were189 unique Class I medical device recalls. Sixty-five (34.4%) recalls were for cardiovascular devices and 36 (19.0%) for implanted devices. Eleven (5.8%) recalls were associated with more than 1 million device units.[iv] From 1992 to 2012, 510(k)-cleared devices were 11.5 times more likely to be recalled than PMA-approved devices. This is particularly concerning for orthopedic devices, as the grand majority are cleared through the 510(k) process.[v]

With this information, device manufacturers would do well to have traditional registry studies and other simple, relatively low effort studies to provide an increased depth and level of knowledge of their devices on the market. As seen in FDA’s own monitoring system, passive monitoring can only do so much. Further, the potential benefit from collaborative cross-manufacturer registry studies done for all devices in a class would benefit patients and manufacturers involved. This is especially true for new technology, new technological applications, or an emerging signal. For example, the metal on metal hip replacement issue. While initially thought to be an improvement, with 1.5 million devices implanted worldwide, many had to be recalled or revised, with lingering questions about their actual safety. . Not only could this kind of registry study lessen the patient risk and manufacturer costs, but it could address issues with public trust if there is a problem. By collaboratively working together, device manufacturers in the same space could have improved outcomes as compared to individual, siloed problem solving.

Two examples of such issues include:

- Loss of sterility. Due to the difference between clinical trials test cases and the large-scale shipment of devices in real life scenarios, packaging tools with sharp points or devices with sharp points in packaging intended to maintain sterility can be problematic. Individual packaging tests may not be sufficient to replicate the pressure forces of shipment in real-life scenarios. Extended or sudden pressure of packaging against sharp points can cause loss of sterility and substantial loss of product. Several possible interventions for this scenario could be seen by a collaborative study from the recall lists and manufacture experience and may result in a cross-manufacturer best standard. Examples would be to include a checklist for which sharp implements are in the package, or a list of device components and tools that require protection for their sharp surfaces and those protections.[vi] Voluntary adherence to a packaging standard for sterility with sharp points published by and for manufacturers could improve outcomes and be a differentiator for consumer confidence.

- Biocompatibility. While the direct material of medical devices is routinely assessed for biocompatibility this level of attention needs to include anything that touches the implant during the production. For example, residual cutting fluid on hip and knee replacements resulted in tens of thousands of people affected and a $725 million class action lawsuit.[vii] Similarly, any instrument or apparatus that holds the implant during its manufacturing or assembly process would need to be considered. For example, nothing can be ferrous that the device touches during the manufacturing otherwise that fixture touch point could leave rust on the final product. Similarly, accessories used for implanting or positioning the product would also need to be considered.[viii]

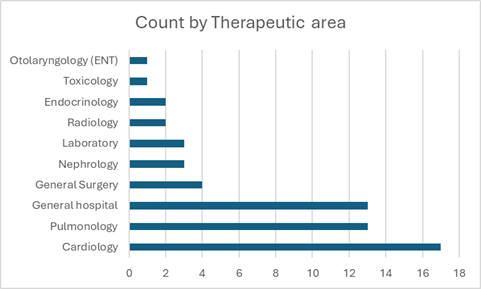

Looking at the most recent data from recalls, the 2023 class I recalls shows a similar pattern to prior years, with some new information.[ix] Of the 59 recalls, 22% were for heart pumps, 17% for general IV pumps, 15% for ventilators. Hemodialysis equipment, defibrillators and assistive breathing (CPAP) had 3% each, with 18% from various other devices including COVID-19 and heart attack lab tests. Putting that information another way, most device recalls were for heart (cardiology) and lung (pulmonology) devices (Fig 1). For device manufacturers working in these areas with these devices, prospective data collection studies may also be very beneficial.

The additional burden of these studies would need to provide a meaningful benefit, but what is at stake is more than substantial. The progression of hip replacement technology is a prime example. Metal on metal replacements were introduced to address the long-term wear problems of earlier metal on polyethylene device models.[x] Later studies showed problems from metal ion release, with one manufacturer’s recall of one of its products and the related litigation costing approximately $2.5 billion dollars.[xi] There are still millions of similar devices in people around the world. Serious measures such as revision surgery for implanted devices as a preventative measure against possible problems is rarely recommended in the absence of evidence of clinical failure. However, screening is now recommended, though still without a clear consensus on best practice by substance, person, or other factors, or what are the best screening tools. These devices are one example where a revision surgery could be recommended. While rare, it is these rarities that can leave a lasting impression on the public and practitioners.

And it is those practitioners and public who are the users and researchers for the next generation of devices. In discussing this issue with one practicing surgeon, the problems of a single recall can leave a permanent impression. For this person, the one time a just-released product was the best choice was the one time a recall forced a revision surgery. That surgeon’s perspective, shared by many, is that you never want to be the first to use a new device. In clinical practice, manufacturers must notify clinicians when a recall is instituted, and then the clinicians must call in their patients. It is a hard discussion for those involved, even if just monitoring is the correct course of action. Telling patients the device implanted in them, while appearing to cause no problems currently, has been recalled can provoke significant anxiety and be difficult for the surgeon to lead effective shared decision-making. Of course, prior to the initial implantation, a discussion of risks and that device failure may occur. However, the initial discussion of risks and the potential for a recall or revision provides little solace if that situation does occur. It is reasonable to assume participation by doctors or patients in new device studies would be similarly affected by a general distrust of new products or manufacturers affected by meaningful recalls.

A general mistrust of new devices counters the very protection and promotion of health that is the purpose of medical devices. Improvement on older models, new devices based on improved technology, and lessons learned from the field, provides ever increasing value but only if they are effective. While recalls may be inevitable, ensuring those situations provide maximum learning not only for the manufacturer affected, but for the device industry in general would be a boon. An increasing trust in medical devices that are approved through the 510(k) process and those with the most class I recalls can help researchers and device manufacturers protect and promote health.

[i] U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Recall Background and Definitions: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/Recalls/ucm165546.htm

[ii] American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Information Statement, Implant Device Recalls. February 2002. Revised December 2008 and February 2016.

[iii] https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/medical-device-safety/medical-device-reporting-mdr-how-report-medical-device-problems 08/28/2024 Accessed 25 October 2024

[iv] Mooghali M, Ross JS, Kadakia KT, Dhruva SS. Characterization of US Food and Drug Administration Class I Recalls from 2018 to 2022 for Moderate- and High-Risk Medical Devices: A Cross-Sectional Study. Med Devices (Auckl). 2023 May 19;16:111-122. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S412802. PMID: 37229515; PMCID: PMC10204764.

[v] Day CS, Park DJ, Rozenshteyn FS, Owusu-Sarpong N, Gonzalez A. Analysis of FDA-Approved Orthopaedic Devices and Their Recalls. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016 Mar 16;98(6):517-24. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00286. PMID: 26984921.

[vi] Si Jana, device consultant, personal communication. 10 October 2024

[vii] https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/banking-fintech/centerpulse-compensates-faulty-implant-victims/3009038 Published November 4, 2002. Accessed 24 Oct 2024

[viii] Si Jana, device consultant, personal communication. 10 October 2024

[ix] https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/medical-device-recalls/2023-medical-device-recalls Published 7 Mar 2024 Accessed 25 Oct 2024

[x] Campbell, Pat PhD*,†,‡; Beaulé, Paul E MD§; Ebramzadeh, Edward PhD†,‡; LeDuff, Michel MA*; Smet, Koen De MD‖; Lu, Zhen PhD†,‡; Amstutz, Harlan C MD*. The John Charnley Award: A Study of Implant Failure in Metal-on-Metal Surface Arthroplasties. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 453():p 35-46, December 2006. | DOI: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238777.34939.82

[xi] https://www.sutherslaw.com/practice-areas/recalled-drugs-medical-devices/depuy-hip-replacement-system-recall/#:~:text=Almost%201%20in%208%20people,to%20have%20a%20revision%20surgery.